Contractual advantage: Overview of the Polish competition authority’s actions on the agri-food market

Since 2017, Poland’s competition authority has initiated dozens of proceedings for practices unfairly exploiting contractual advantage. As a result, nearly 20 decisions have already been issued, and many notices have been issued to companies. The fines alone have amounted to some PLN 1.1 billion (although appeals against some decisions are pending). To date, the largest fine for unfair exploitation of contractual advantage is over PLN 723 million (assessed against Jerónimo Martins Polska SA in 2020). What practices is the regulator seeking to identify and punish?

It is widely accepted that maintaining good relations between all links in the agricultural and food supply chain is crucial to its proper functioning. But in practice, the structure of this market in Poland gives rise to significant differences in bargaining power between suppliers and purchasers. Strongly consolidated entities in the distribution and processing sector compete with fragmented producers of agricultural raw materials and foodstuffs. The differences in economic potential can result in exploitation of contractual advantage by larger buyers against smaller suppliers.

In the case of practices that unfairly exploit contractual advantage in the agri-food sector, the broad powers granted to Poland’s competition authority (the President of the Office of Competition and Consumer Protection—UOKiK) are intended not only to counteract unfair actions, but above all, to bring balance to this market, which is in the vital interest of the state and consumers. This can be seen in the high financial sanctions that the regulator can impose on businesses (up to 3% of annual turnover).

Unfair practices

The Act on Prevention of Unfair Exploitation of Contractual Advantage in Trade in Agricultural and Food Products introduces a catalogue of unfair practices. These practices are divided into “black” practices (absolutely prohibited) and “grey” practices (allowed conditionally, i.e. subject to clear and unambiguous prior agreement between purchaser and supplier). But the catalogue of practices indicated in the act is open-ended. This means that other practices, not explicitly mentioned in this catalogue, may be considered unfair if they are contrary to good practice and threaten or violate the material interest of the other party (general clause in Art. 6).

The act defines “contractual advantage” as the presence of a significant disparity in the economic potential of the purchaser relative to the supplier (or the supplier relative to the purchaser). The act also sets turnover criteria beyond which there is presumed to be a contractual advantage.

Practices that unfairly exploit contractual advantage include for example:

- The purchaser’s demand that the supplier pay for deterioration or loss of agri-food products that occurred at the purchaser’s facilities or after transfer of ownership of such products to the purchaser, for reasons not attributable to the supplier

- Threatening or taking retaliatory commercial actions against the supplier if the supplier exercises its contractual or legal rights

- The purchaser’s request that the supplier cover the purchaser’s marketing of agri-food products.

Below, we discuss selected decisions by the President of UOKiK concerning significant banned practices.

Auchan: Logistics fees

In December 2023, supermarket chain Auchan Polska was punished for imposing logistics fees on protected suppliers of agri-food products, i.e. fees for transporting goods from central warehouses to Auchan chain stores. The President of UOKiK found that this practice is unfair and violates the principles of fair competition. The decision stated that the transport of goods from warehouse to store is an integral part of a retail chain’s business model and not a service performed for suppliers. Thus there should be no extra fee for this activity.

Cooperation between suppliers and Auchan Polska was based on contracts for performing logistics services. According to the regulator, Auchan Polska only took action to perform the contract after delivery of the goods by the supplier to the central warehouse. Prior to delivery of goods to the central warehouse, Auchan Polska did not participate in the logistics of the supplier’s goods. All activities and duties related to delivery to the central warehouse (including the cost of delivery, organisation of transport, preparing and completing shipment) rested with the supplier, which, according to the regulator, justified the conclusion that charging for logistics services at the central warehouses was unreasonable.

Also, based on the evidence, the regulator found that in nine out of ten segments, the logistics fees were higher than the actual cost of logistics service. The rules under which Auchan Polska charged a margin were unclear, and the nature of the margin indicated discrimination against the suppliers who paid it. According to the authority, charging a margin also indicated generation of additional income for Auchan Polska from the services it provided, which contradicted the chain’s claim that the fee only covered the costs incurred by the chain.

The President of UOKiK imposed a fine of over PLN 87 million on Auchan Polska (decision no. RBG-12/2023).

An investigation into similar practices by retailer Carrefour Poland is also pending.

Kaufland: Retroactive discounts

One of the banned practices indicated in the act is unjustifiably reducing the amount due for delivery of agricultural or food products after they have been accepted by the purchaser either in full or in an agreed portion, in particular by demanding a discount after the fact.

According to the regulator, such a procedure was used by supermarket chain Kaufland. According to the authority’s (non-final) findings, the retailer’s practices consisted of:

- Setting the terms of annual cooperation with some suppliers after the start of the year covered by the terms. In such situations, with prolonged contract negotiations for the new year, the supplier did not know the terms under which it was delivering goods to the retailer from the beginning of the year to the date of signing the agreement. In the new agreement, additional discounts were often introduced, or Kaufland increased the amount of existing discounts, and suppliers had to cover this adjustment. In practice, this meant retroactive reduction of the price already paid for purchase of products by Kaufland during the interim.

- Charging some agri-food suppliers additional discounts that were not stipulated in the contract, but were agreed after the end of the accounting period. Such price discounts were an amendment of business terms in favour of Kaufland, not regulated in the framework agreement with the supplier. Discounts were extracted without agreeing with the suppliers before the start of the accounting period on the amount or conditions for granting discounts. Therefore, according to the authority, the suppliers did not know when the retailer would demand a discount, or in what amount.

In December 2021, the President of UOKiK imposed a fine for these banned practices in the amount of nearly PLN 124 million on Kaufland (decision no. RBG-4/2021).

Eurocash: Slotting fees

According to the President of UOKiK, the food distributor and retailer Eurocash collected a number of additional and unjustified fees from suppliers, and some of Eurocash’s actions resembled the blacklisted practice set forth in the act of demanding payments from the supplier unrelated to the buyer’s sale of the supplier’s agri-food products (i.e. “slotting” or “shelving” fees). As the regulator found:

“Some of the services paid for by the suppliers were not performed at all, and some were to be provided without any additional fee. Suppliers were also not informed of the costs and results of some services. The aim of these actions by Eurocash was to reduce the fees to entities supplying agricultural and food products to its stores.”

The practices challenged by the authority consisted of:

- Failure to ensure that suppliers’ products continued to be offered by the chain, despite charging a fee for them

- Charging fees for the supplier’s sponsorship of the chain’s integration meetings, but if the supplier chose to participate it would have to incur additional costs

- Charging for training store personnel on techniques for selling the supplier’s goods, when in reality it was general training on the sale of various categories of products (e.g. meat, cold cuts, fruits and vegetables), rather than the specific products of the supplier paying for the training

- Charging fees for educating and informing franchisees about new products from suppliers, when in reality the suppliers had no knowledge of performance of such services and did not provide information about new products to Eurocash, which ordered and distributed products at its own discretion

- Charging fees for monitoring market demand and sales trends for the supplier’s products and supervising orders, when this activity was actually carried out by Eurocash with respect to all products available in stores, and obviously, even without charging these fees, Eurocash would have had to carry out such monitoring anyway, in its own economic interest.

In connection with these practices, at the end of 2021 the President of UOKiK imposed a fine (not yet final) of more than PLN 76 million on Eurocash (decision no. RBG-3/2021).

Intermarché: Late payment

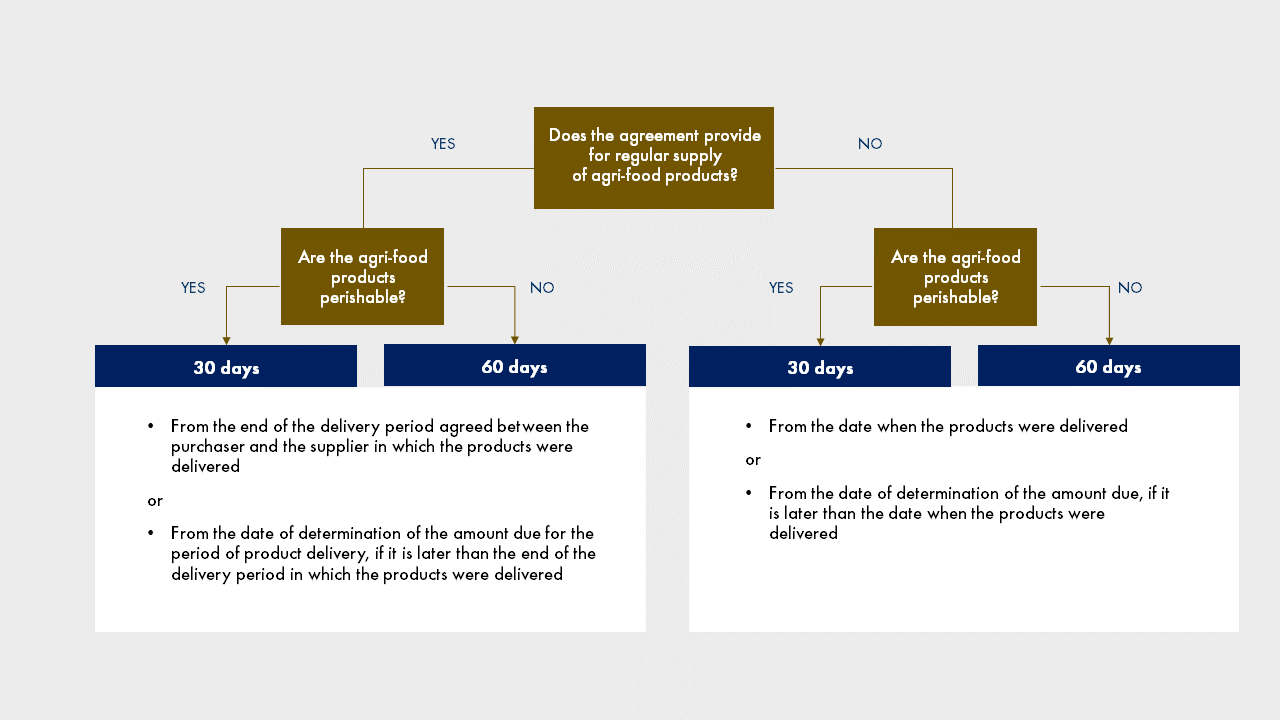

One of the unfair practices banned by the act is late payment to suppliers. The payment deadlines under the act vary depending on whether the contract with the supplier provides for regular delivery of products, and whether the products are perishable.

In 2021, the regulator accused the supermarket chain Intermarché (SCA PR Polska) of failing to pay suppliers of agri-food products on time. For most delays (more than 70% in 2020), payment was no more than 10 days late, but the authority found that in extreme cases, there were also delays of more than 100 days. Additionally, in the event of discrepancy as to the price or quantity of goods shown on the invoice, until the situation was clarified the company would pay suppliers only for the invoiced goods. Intermarché also took a long time to clarify discrepancies in invoices (in some cases up to a year or more), resulting in unjustified extensions of payment deadlines.

The President of UOKiK ordered SCA PR Polska to change its practices that may have constituted unfair use of contractual advantage. The company undertook to pay overdue amounts with interest to suppliers of agri-food products, and to change the method of resolving disputed invoices (decision no. RPZ-7/2021).

Another practice of SCA PR Polska against which the regulator issued a decision in 2023 concerned setting discount terms for the following year of cooperation after the year had already started, with the obligation to apply the new terms retroactively, and claiming discounts despite failure to meet the conditions stipulated in the agreement. The company undertook to return the amounts collected, with interest, for the discounts challenged by the regulator and to cease entering into agreements with suppliers with discount terms applied retroactively after the year had already started (decision no. DPK-1/2023). These decisions are final.

Jerónimo Martins: Retrospective discounts

In December 2020 the regulator sanctioned Jerónimo Martins Polska (the Biedronka grocery chain) for the practice of charging discounts from suppliers of agri-food products based on contracts signed at the end of the accounting period, without agreeing before the start of the accounting period on the amount of the discounts and the conditions for granting them.

The authority found that the need to grant such discounts was not provided for in the contract underlying the chain’s cooperation with the supplier. During a given accounting period, the supplier did not know whether it would be obliged to provide a discount or what the amount would be.

The President of UOKiK imposed a fine for these banned practices of over PLN 723 million on Jerónimo Martins (decision no. RBG-13/2020).

Conclusions

Poland’s competition authority has already announced that in 2024, it will continue its efforts to improve the situation of weaker entities in the agri-food market. The experience gained in investigating the foregoing cases can translate into increasing intensity of enforcement in this area.

Therefore, entities that can be found to have a contractual advantage in the agri-food market should analyse their practices towards counterparties to avoid possible fines—even for unintentional actions—as such fines can be as high as 3% of the company’s turnover in the financial year preceding imposition of the fine.

Agnieszka Jelska, attorney-at-law, Tomasz Kisiel, Competition & Consumer Protection practice, Wardyński & Partners